Sitting in a quiet library researching for my book, Women of War, headphones on, I pressed play on the first of the digital archival collection of oral histories from Italian anti-fascist partisans, as they were called, fighting the Nazis during the German occupation of World War II. The image attached to the recording showed an elderly woman named Lidia, who started by talking about her childhood under the oppressive Fascist regime.

“I’m going … give me the gun,” Lidia said a few minutes into her testimony. I held my breath as she explained that her partisan band had just received intel that the Nazis were going to “mop up,” as Lidia described, an area of fellow partisans and residents with heavy artillery. Someone had to warn them. She grabbed the gun and hopped on her bicycle.

“I met this German patrol. What could I do? They ordered me to stop. I pulled my gun and started to shoot. I shot while I was riding the bicycle; I shot as long as I could carry on until I reached the right place and informed all the others. After that we spread the news quite quickly. I managed to get through all these bullets … I made it. The battle went well, and they survived.”

I was drawn to this subject in no small part because of my Italian American heritage and the sense of political and social justice ingrained in my upbringing. But it wasn’t until I saw Lidia on the screen that it occurred to me that she and my grandmother were contemporaries, both born in 1920; both living their childhoods under Mussolini. But when they were 23, Lidia was taking up arms against the Nazis — and my nonna was a soldier’s wife in the United States, having escaped Fascist oppression with her family years earlier. Would my nonna have been fighting alongside her if her family hadn’t left their homeland?

The PEOPLE App is now available in the Apple App Store! Download it now for the most binge-worthy celeb content, exclusive video clips, astrology updates and more!

Born Asunta Maria, my nonna arrived with her mother and siblings — three sisters and a brother — passing through Ellis Island after more than a week in a cramped steerage compartment. Like so many, the dream of America was reason enough to leave behind everything that they knew. But I had long assumed it was only my great grandfather’s well-paying job that drew them to America. When I realized they arrived in the United States only after stricter American immigration laws were in place, doing whatever they could to leave an increasingly oppressive fascist regime who believed in the inherent inequality of people, I began to understand the nonna I knew in a new way.

Under Mussolini, as I learned through my research, women had civil liberties taken from them. First there were higher tuition fees and admittance caps on the number of women who could pursue secondary schooling. Then, the Fascist bureaucracy placed limits on the number of women certain companies could hire (even at a much lower salary for the same work).

Women were told to wear long sleeves and skirts, and motherhood was emphasized as a woman’s life goal under fascism. Birth “a million bayonets” for Mussolini’s army, in their fevered militarism to help “Bring Back the Roman Empire!” as the rally cry went. Families were given monetary incentives to have more babies and they were expected to send their children to the Fascist youth clubs where further political and gender-based indoctrination continued.

Before long, jails were filled with women who had dared rebel against these strictures. In addition to many more obvious imprisonable offenses, like defacing an image of Il Duce, a woman could be jailed for obtaining an abortion, or helping other women do the same. More women were locked in asylums for “female deviancy” for working while also raising children or not submitting to the will — sexual or otherwise — of their husbands.

Further research taught me more about the realities of life under Mussolini’s rule: how he took control of the press, remade school curriculum to omit stories of revolution or political systems that might be counter to Fascism, arrested detractors, sometimes beating them or forcing them to drink castor oil, and fired vocal anti-Fascists from their jobs, making their financial future dependent on their fealty to the Fascist regime.

I felt shame as I learned this history and the more I learned about Il Duce’s treachery, I realized that while I had long believed my ancestors had immigrated because they were running toward the golden streets of America, it seemed likely they were also running from something: Fascist oppression in their homeland.

Susan, as her mother renamed my nonna in America, was known as deeply empathetic, always willing to help her neighbors. Her perfect penmanship and knowledge of both Sicilian dialect and standard Italian made her the go-to in the neighborhood to read or translate letters and documents — which also gave her continued lessons on the horrors her family had left behind. But she was also known for her fiery temper, often in the face of injustice. She would stand up to the bullies who teased her for speaking Italian, or smelling like the sauce her mother always made them for lunch. I couldn’t imagine that she would not have done the same when the stakes were higher.

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE’s free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer , from celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

She would graduate from high school and marry an Italian American iron worker who had taught fighter pilots during World War II. He would tell his young wife about the splatters of blood and bullet holes still in the cockpits of the planes that cycled through his airbase for maintenance, knowing the damage coming from Nazi anti-aircraft fire or dogfights over Italy.

The horrors of World War II galvanized my grandmother. While her peers, like Lidia — and the other intrepid women I met in my research — were taking up arms, writing underground newspapers and sewing secret messages into their dress hems, my nonna was learning how her local government worked and reading voraciously, wondering what she could do to help in the war. Every weekend, she anxiously awaited calls from Italy, wringing her hands over the hope of news of their extended family’s struggles from afar.

In the decades after the war, when they moved to western New York, my nonna used what tools she had to fight for women’s rights and political justice, acutely aware of how women were viewed in a patriarchal world. She became engaged in local politics, wanting to take advantage of the freedoms she knew her Italian family and friends had risked their lives for. Once her daughter — my mother — was born, she repeated these lessons of political education and agency, which seemed radical in the 1950s.

The PEOPLE Puzzler crossword is here! How quickly can you solve it? Play now!

As the most bookish of her grandchildren, I was the one to whom she gave signed photos of her favorite political candidates, which I dutifully hung on my mirror next to my My Little Pony stickers. I was the one who dressed up like the “first woman president” on career day, wearing a too-big suit and carrying a briefcase. Although I would become a writer and professor instead of a politician or lawyer, I see now how the focus of my research has long been in service of those who had no voice, as my nonna encouraged.

My nonna died before I graduated high school, before I could ask her about her childhood under the specter of fascism. It didn’t occur to me until that moment listening to Lidia’s story that my nonna could have been her. And that the woman I had become was a direct result of her rejection of her childhood under Mussolini’s oppression.

Until the moment I saw Lidia on the screen — one of the first of many oral histories I would hear in my research for my book Women of War — I had assumed that my grandmother’s feminist tendencies had been a product of her assimilation into American culture and her ambitions for her family. But hearing the stories of my nonna’s Italian peers, and learning about the political and gender-based oppression my family escaped from and my nonna always sought to redress, made me understand her and the legacy she left me in a new way.

I would give anything to talk to my nonna again, ask her about her childhood, what she knew about the intrepid women from her homeland, and what she learned about bravery in America. My heritage, my legacy, lies with these women who refused to let those in power define them, who were willing to die for their liberty. I realize that I am fulfilling my legacy to help tell these stories and to continue the fight on the side of justice.

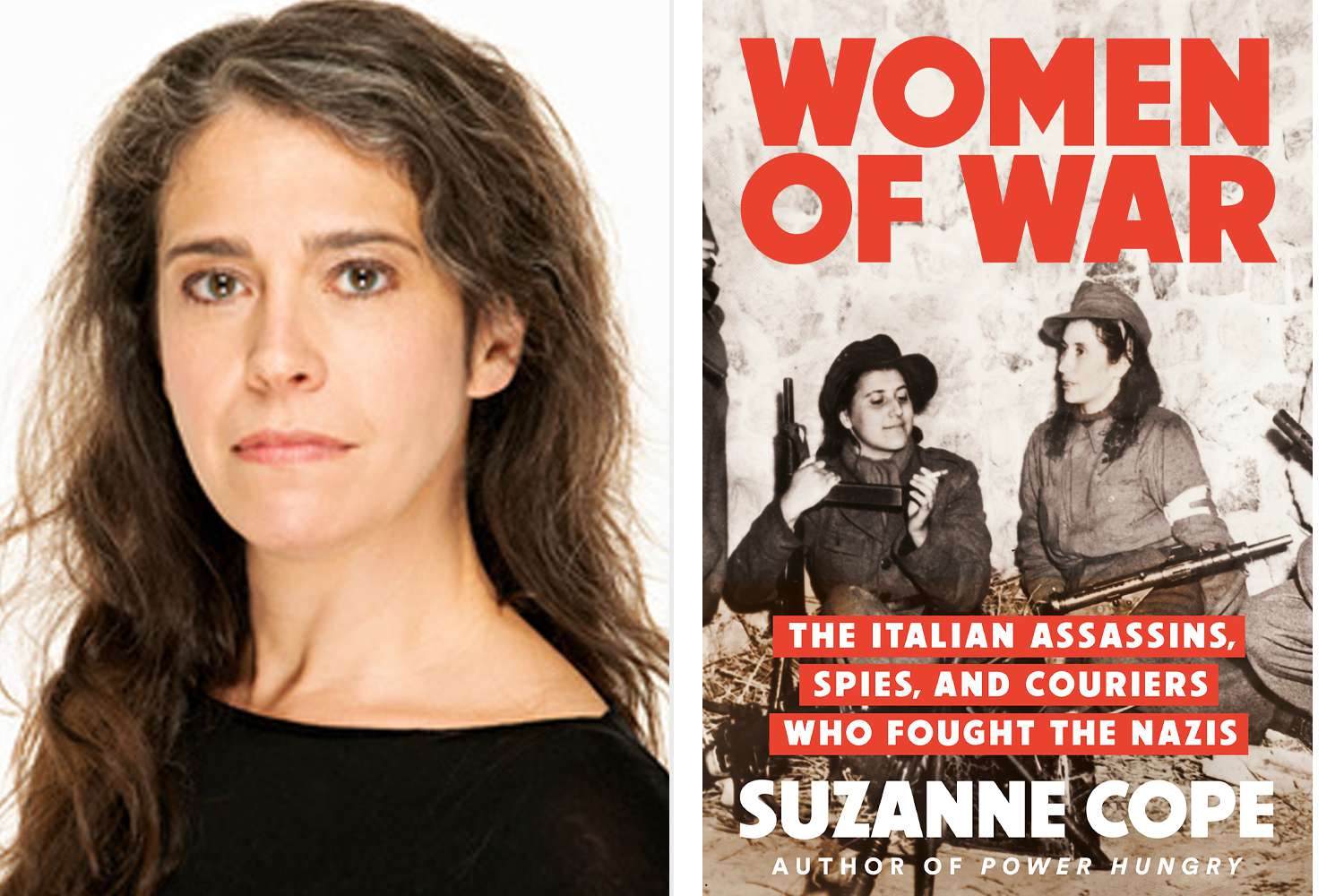

Women of War by Suzanne Cope comes out April 29 and is available for preorder now, wherever books are sold.

Read the full article here